|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

This is adapted from a presentation given to the Cocoa Beach City Commission Thursday, April 5, 2007. Go Here for pictures of the three different kinds of Australian Pines in the Thousand Islands and further discussion about their detrimental effect on the environment, and Here for a discussion of restoration goals. Please remember, the ecological damage done by these non-native invaders can’t be outweighed by aesthetic arguments such as “they look nice” or “they shade us from the stadium lights at the high school.” These complaints are short-sighted and selfish. These trees have no place in a Florida ecosystem and should be removed as soon as is practical.

Ecological Impacts of Australian Pine (Casuarina spp.)

in the Thousand Islands

ABSTRACT

Three kinds of Australian Pine are found in dredged portions of the Thousand Islands. One is the species Casuarina equisetifolia; there is also Casuarina glauca, and one that is thought to be a hybrid between C. equisetifolia and C. glauca. On several islands these invasive non-native trees are found in dense stands where they have eliminated native vegetation and excluded native vertebrates. State management plans call for the eradication of the entire genus due to its destructive effects on native species and ecological processes in Florida. Those destructive effects are explained in some detail below.

INTRODUCTION

Thousand Islands

Though many of these islands have been modified by mosquito control and dredge and fill, the Thousand Islands formation is natural. The Thousand Islands landform is technically described as the relict shoals of a flood tide delta deposit – essentially the remains of a former inlet. The time of inlet formation is not known, but inlets in the Indian River Lagoon generally move to the south and finally close due to longshore sediment transport, 200 to 300 years after creation (R. Parkinson, personal communication). A topographical low still exist in the area of 11th Street south; this might be the last location of the inlet before it closed.

The Thousand Islands have been heavily impacted by development and mosquito control. Beginning in the late 1950s, small ditches were dug through the islands to allow mosquito fish (Gambusia affinis) access to inner areas of the marsh for mosquito control (J. Salmela, personal communication). At approximately the same time, dredge and fill activities were begun in Cocoa Beach for housing development. This involved dredging of canals to provide fill material for houses. During the late 1960s deeper ditching by dragline was used as a stronger effort to control mosquitoes. The islands south of Minutemen Causeway were more heavily impacted than those islands to the north. Relatively large areas of native marsh were converted to uplands in this way.

Vegetation Communities

The vegetation communities of the Thousand Islands can be classified in three habitat types: natural tidal marsh, tropical hammock, and dredge-spoil. Of these three, the dredge-spoil community suffers the greatest degree of invasion by non-native plant species.

The tidal marsh habitat is found on the few islands that remain unaltered, inside the C-34 impoundment, and along most of the edges of the islands. The margins of the islands and their interiors along ditches are typically fringed with mangroves. Unaltered islands have mangroves inland if they are inundated sufficiently to allow propagule dispersal to the interior. The dominant plants of the unaltered interior marshes appear to be glasswort (Sarcocornia perennis) and saltwort (Batis maritima), and all three species of mangrove.

Tropical vegetation is found throughout the southern Thousand Islands. The two major areas are associated with shell middens. The small area on Crawford Island consists of a few trees that have volunteered in dredge spoil. These trees might represent an older hammock destroyed by dredging but visible in the 1951 aerial photograph. Tropical genera present in the Thousand Islands include Amyris, Bursera, Capparis, Chiococca, Erythrina, Eugenia, Ficus, Guapira, Myrcianthes, and Randia (Kozusko, unpublished manuscript). Many of these species are listed by Wunderlin and Hansen (2003) as having the northern limit of their range in or near Brevard County. This is one of the major reasons the Thousand Islands are so worthy of conservation – they represent the northern-most limit of the distribution of several species of tropical plants. The presence of invasive non-native vegetation near these hammocks is a serious threat to their existence.

Dredge spoil is largely covered by Brazilian pepper (Schinus terebinthifolius) and Australian pine. Native shrubs found on dredge spoil include swamp privet (Forestiera segregata), saltbush (Baccharis halimifolia), wax myrtle (Myrica cerifera), and southern red cedar (Juniperus virginiana).

LITERATURE REVIEW

Australian Pine

Australian Pine is native to Australia, Southeast Asia and the south Pacific Islands. It was first brought to the United States beginning in the late 1880s, and was spreading in Florida by the turn of the century (Morton, 1980). It was widely used as a windbreak, especially for citrus trees, and was planted in the mistaken belief that the trees could prevent erosion.

Its Generic name Casuarina comes from the Malay word kasuari, their word for the cassowary, referring to the resemblance of the tree's “needles” to the Cassowary’s plumage. The specific name equisetifolia is derived from the resemblance of the needles to horse hair, and glauca refers to a bluish waxy coating on the “needles.” In spite of its common name, Australian pine is not a true pine but rather a flowering tree.

All species of the genus Casuarina are regulated in Florida. The Florida Department of Environmental Protection (FDEP) lists all “Casuarina spp.” as Class I Prohibited Aquatic Plants. This makes it illegal to posses, collect, transport, cultivate, or import them without a permit from the Department (62C-52.001 FAC). The Florida Exotic Pest Plant Council rates Australian pine as a Category I plant. This category is defined as an “invasive exotic that is altering native plant communities by displacing native species, changing community structures or ecological functions, or hybridizing with natives.” This definition relies on scientifically documented ecological damage caused by the plant in question (Florida Exotic Pest Plant Council, 2005). These classifications do not come lightly, and reflect the grave concern biologists have over the ability of these trees to invade, degrade, and even destroy natural systems.

Australian pine has shallow roots that rarely penetrate very deep into the soil. Planted in many areas to prevent erosion, this tree actually increases erosion by eliminating native vegetation with deeper roots, or mangroves with roots that absorb wave energy (Klukas, 1969). Along the shoreline in the Thousand Islands the banks generally erode from beneath the shallow roots of Australian pine until the tree falls over. The shallow roots also make these trees prone to wind-throw during storms (Digiamberardino 1986).

Reproduction

Australian pine does not rely on living organisms for pollination; it casts its pollen to the wind. Known as anemophilous pollination, the taller the tree the more effectively the pollen is broadcast to the female flowers. It has been reported that Australian pine pollen can cause allergic reactions in people (Elfers, 1988). The seed has a membranous wing to aid its dispersal that can be either by wind or in water (Binggeli, 1997). No birds use Australian pine seeds as a food source with the exception of migrating gold finches which are not seen in the Thousand Islands. The seeds are eaten by ants (Elfers, 1988).

Allelopathy

Australian pine is very effective at controlling which plants it has to compete against for light and nutrients. When established it alters the temperature, light, and chemistry of soils, which drastically affects the native plants and animals beneath it. Casuarina glauca is thought to posses allelopathic properties. Allelopathy is the ability to exude chemicals that inhibit growth of other species beneath it. The chemicals called tannins that are leached from its “needles” are carcinogenic and can kill cattle that forage on them (Elfers, 1988). Australian pines are known to decrease soil pH, which has a dramatic effect on the capacity of the soil to retain nutrients (Ussiri, Lal, and Jacinthe, 2006).

Trophic-level Ecological Effects

Australian pine has the ability to fix soil nitrogen at rates comparable to nodulated legumes. This explains the capacity of Australian pine to occupy nitrogen-poor sites such as disturbed areas and coastal dunes (Ng 1987). This allows these trees to grow densely and quickly. The dense growth habit of Australian pine reduces light falling on the ground, and the high litter fall prevents germination of seeds. In the way these trees block sunlight and usurp the soil surface with litter fall, they are the ecological equivalent of a shaded parking lot. The ground level beneath stands of these trees is often utterly devoid of vegetation and any animals except for a few arthropods. The ground below these trees becomes ecologically sterile.

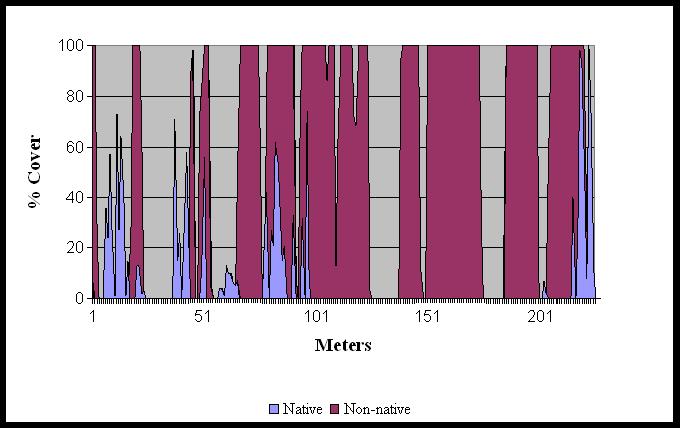

In Figure 1, data from a vegetation transect at the east end of Crawford Island are presented. The X Axis represents each meter along the transect from south to north. The Y Axis represents the percentage of each meter that is covered by native vegetation less than 1 meter in height (blue) and non-native vegetation greater than 3 meters in height (red). Native vegetation is depicted at this height because it represents replacement plants.

Three important factors are apparent. Native vegetation is more open, allowing access by ground-foraging birds and reptiles. Non-native vegetation tends to dominate at 100% cover. And where non-native plants comprise the canopy, there is little or no native vegetation beneath it. For approximately 100 meters, nearly half the transect, there is no native vegetation replacing itself. This area is utterly dominated by Australian pine, to the detriment of every other species found on the island. Figure 2 is a photograph of this destroyed habitat at approximately meter number 165.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 1. Vegetation transect data from Crawford Island, Cocoa Beach. March, 2007.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 2. View of sterile habitat beneath Australian pines on Crawford Island, Cocoa Beach. March, 2007. The only small plant visible in the foreground is carrotwood (Cupaniopsis anacardioides), also an invasive non-native plant.

|

|

|

|

Australian pine destroys nesting habitat for many species not seen in the Thousand Islands such as sea turtles and crocodiles. These trees change the profile of dunes, making them steeper and horizontally compressed (Doren and Jones, 1997). Locally, they affect nesting habitat needed by the diamondback terrapin (Malaclemys terrapin), a unique species unfortunately in decline. According to Klukas (1969), Australian pine is also known to exclude the gopher tortoise (Gopherus polyphemus), which has been introduced on at least one island.

Mazzotti, Ostrenko, and Smith (1981) studied the effects of Australian pine on small mammals and found that these trees effectively eliminated breeding animals from the landscape. The entire population demonstrated a strong preference for native vegetation. This finding is especially important because small mammals are a vital link between plants and predatory animals in ecosystem-level energy pathways. This systematic degradation of upper-trophic level biodiversity is the main reason these trees are seen as having no place in a Florida landscape.

Editorial Note

It is worth pointing out that the Environmentally Endangered Lands Program is not, and never was intended to be a landscaping program. Its stated mission is “Protecting and Preserving Biological Diversity Through Responsible Stewardship of Brevard County’s Natural Resources.” Responsible stewardship is further defined as being “…guided by scientific principles for conservation and the best available practices for resources, stewardship and ecosystem management.” It is difficult to fathom how the willful protection of any non-native species, be it stray cat, Brazilian pepper, or Australian pine, could possibly be a part of that mission.

Many biologists, myself included, view non-native species as an even bigger threat to the ecological diversity of Florida than development because these invaders threaten lands already protected from the bulldozer. The State is currently involved in a pitched battle against species such as Australian pine, spending millions of dollars trying to bring them under control. State funds were given toward the acquisition of these islands; it is simply unreasonable to expect anyone to sanction the protection of these trees.

No one likes change. And even though it will be gradual, as these trees are removed the islands will look different. But we must not see this in the darkness of something that has been lost, rather we should think of it in the light of what has been gained.

The next time you look at a stand of Australian pines I challenge you to see them not as stately trees swaying gently in the sea breeze, but as trespassers that are taking something from us. I challenge you to understand that the pelicans resting on branches hanging over the water will find other places to rest – just as they did for thousands of years before these trees were brought to Florida. I challenge you to consider all the native species, the ones we’re trying to protect, that will be able to reclaim the land currently held against its will by these trees. And I challenge you not to be selfish about how you feel the land should look, but rather to accept the removal of these trees as a science-based act of ecological healing, fulfilling the Mission of our Environmentally Endangered Lands program. By every contextually relevant definition of the word “right”, this is the right thing to do.

LITERATURE CITED

Binggeli, P. 1997. Casuarina equisetifolia L. (Casuarinaceae), Woody Plant Ecology.

Accessed March 29, 2007: http://members.lycos.co.uk/WoodyPlantEcology/invasive/index.html

Bucholtz G. A., A. E. Hensel, R. F. Lockey RF, D. Serbousek , and R. P. Wunderlin. 1987.

Australian pine (Casuarina equisetifolia) pollen as an aeroallergen. Annals of Allergy. July; 59(1):52-566.

Ceilly, D. W., Buckner G. G., and J. R. Schmid. 2005. A survey of the effects of invasive exotic

vegetation on wetland functions: aquatic fauna and wildlife. Final report submitted to Charlotte Harbor National Estuary Program. 53 pp.

Digiamberardino, T. 1986. Changes in a south east Florida coastal ecosystem after elimination

of Casuarina equisetifolia. Unpublished, Nova University.

Doren R. F., D. T. Jones. 1997. Management in Everglades National Park. In: Simberloff D,

Schmitz DC, Brown TC, editors. Strangers in paradise: impact and management

of nonindigenous species in Florida. Washington, D.C.: Island Press. p 275-86.

Elfers, S. C. 1988. Element Stewardship Abstract for Casuarina equisetifolia. Report to The

Nature Conservancy, 14 p. On file at: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Intermountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory, Missoula, MT.

Florida Exotic Pest Plant Council. 2005. Invasive Plant List.

http://www.fleppc.org/list/list.htm, retrieved March 23, 2007.

Klukas, R.W. 1969. Exotic Terrestrial Plants in South Florida with Emphasis on Australian Pine

(Casuarina equisetifolia). As cited in Austin, 1978. Technical Report, South Florida Water Management District, Everglades National Park, Homestead, FL.

Kozusko, T. J. 2007. The Depositional History, Anthropogenic Impacts and Vegetational

Communities of the Thousand Islands in Cocoa Beach, Florida. Unpublished manuscript.

Kozusko, T. J. 2007. Vegetation of Crawford Island, Thousand Islands in Cocoa Beach.

Unpublished report.

Mazzotti, F. J., W. Ostrenko, and A. T. Smith. 1981. Effects of the exotic plants Melaleuca

quinquenervia and Casuarina equisetifolia on small mammal populations in the eastern Florida Everglades. Florida Scientist 44(2):65-71.

Morton, J. F. 1980. The Australian pine or beefwood (Casuarina equisetifolia L.), an invasive

"weed" in Florida. Proc. Florida State Horticultural Soc.

Ng, B.H. 1987. The effects of salinity on growth, nodulation and nitrogen fixation of

Casuarina equisetifolia. Plant and Soil 103(1):123-125.

Ussiri, D. A., R. Lal and P. A. Jacinthe. 2006. Soil properties and carbon sequestration of

afforested pastures in reclaimed minesoils of Ohio. Soil Sci Soc Am J 70:1797-1806.

Wunderlin, R. P. and B. F. Hansen. 2003. Guide to the vascular plants of Florida. Univ.

Presses of Florida, Tampa. 806 pp.

|

|

|

|